The World Wide Web that Sir Tim Berners-Lee invented in 1990 was a collection of linked documents. The Web we have today is a collection not just of documents (some of which we quaintly call pages), but of real estate we call sites. This Web is mostly a commercial one.

The World Wide Web that Sir Tim Berners-Lee invented in 1990 was a collection of linked documents. The Web we have today is a collection not just of documents (some of which we quaintly call pages), but of real estate we call sites. This Web is mostly a commercial one.

Even if most sites aren’t commercial (I don’t know), most search results bring up commercial sites anyway, thanks both to the abundance of commercial sites on the Web, and “search engine optimization” (SEO) by commercial site operators. Online ad spending in the U.S. alone will hit $40 billion this year, and much of that money river runs through Google and Bing.

But that’s a feature, not a bug. The bug is that we’ve framed our understanding of the Web around locations and not around the fabric of connections that define both the Net and the Web at the deepest level. That’s why nearly every new business idea starts with real estate: a site with an address. Or, in the ranching-based lingo of marketing, a brand.

The problem isn’t with the sites themselves, or even with the real estate model we use to describe and understand them. It’s with their underlying architecture, called client-server.

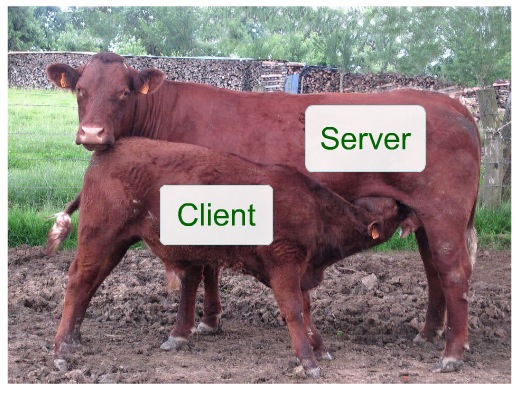

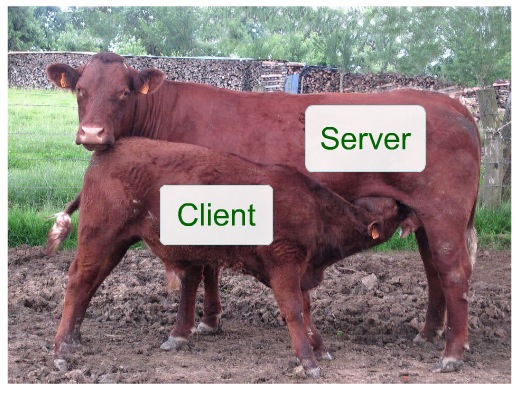

Client-server, by design, subordinates visitors to websites. It does this by putting nearly all responsibility on the server side, so visitors are just users or consumers, rather than participants with equal power and shared responsibility in truly two-way relationship between equals. Thus the client-server relationship is roughly that of calf to cow:

From the teats of the cow-server, the calf-client sucks the milk of HTML and Javascript, plus cookies: text files deposited by a website’s server in a visitor’s browser. Their original purpose was to help both the site and the visitor (the cow and the calf) remember where they were last time they met, and to retain other helpful information, such as logins and passwords.

But cookies also became a way for commercial cows and their business friends (aka third parties) to keep track of their calves, reporting back where those calves traveled, the cows they suckled, the stuff they click on. Based on what they learn from tracking, the cows can — alone or with assistance from third parties, produce “personalized” milk in the form of customized pages and ads. This motivation is all the rage today, especially around advertising.

Nearly all the investment on ‘relating’ is still on the sell side: the cow side, because that’s where all the power is concentrated, thanks to client-server. So we keep making better cows and cow-based systems, forgetting that the calves are actual human beings called customers. We also overlook opportunity in helping demand drive supply, rather than just in helping supply drive demand.

But some of us haven’t forgotten. One is Phil Windley, a Ph.D. computer scientist, former CIO of Utah, co-founder of Kynetx, and the inventor and lead maintainer of a language called KRL (Kinetic Rules Language), plus the rules engine for executing KRL code. (Both are open source.) The rules are the individual’s own. The rules engine can go anywhere. No cow required.

To describe the box outside of which Phil thinks, he gives a great presentation on the history of e-commerce. It goes like this:

1995: Invention of the Cookie.

The End.

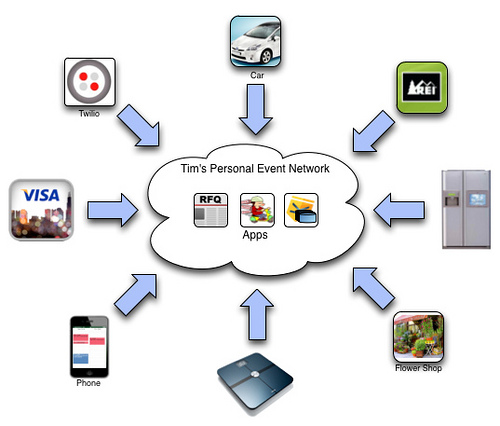

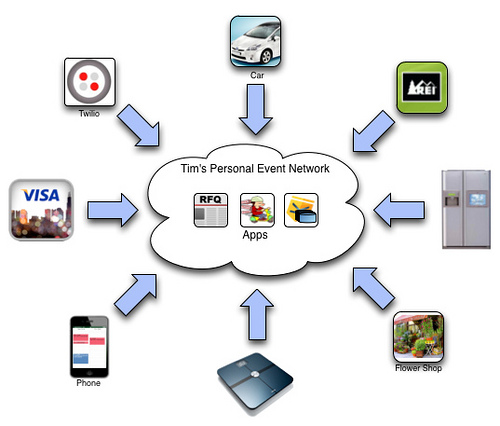

To describe where he’s going (along with Kynetx and the rest of the VRM development community), Phil wrote a new book, The Live Web (a term you might have first read about here), and has been publishing a series of blog posts that deal with what he calls Personal Event Networks. Think of your Personal Event Network as the Live Web that you, as a human being (rather than as a calf) operate. Live. In real time. Your own way. You can take advantage of services offered by the servers of the world (through APIs, for example). But it’s your network, and it’s built with your own relationships. It doesn’t replace client-server, but it gives servers lots to do besides being cows. In fact, the opportunities are boundless, because they’re in wide-open virgin territory.

A Personal Event Network puts you at the center of your Live Web, with your own apps, and your own rules for what follows from events in your web of relationships. “Personal event networks interact with each other as equals,” Phil says. “They aren’t client server in nature.” Here’s how Phil draws one example:

Look at the three items indside the personal cloud:

- At the center are apps. We’re already familiar with those on our computers and mobile devices. While they might have connections to outside services, they are personal tools of our own. They are neither calves nor cows.

- On the left is an RFQ, or a Request For Quote, also called a Personal RFP.

- On the right are rules, written in KRL.

Together those control how we interact with all the devices and services on the outside, on the Live Web. Note that those outside items are not functioning as cows, even though they also live in the commercial Web’s client-server world. They are being engaged outside the cow function, mostly through APIs.

Here’s how Phil explains how this works for a guy named Tim, who has a relationship with a flower shop, described here:

Tim’s personal event network has a number of apps installed. It’s also is listening on many event channels. These channels are carrying events about everything from Tim’s phone and appliances to merchants he frequents.

REI and the flowershop both have separate channels into Tim’s personal event network. Consequently, Tim can

- Manage them independently. If REI starts spamming Tim with events he doesn’t like, he can simply delete the channel and they’re gone.

- Permission them independently. Tim might want to get certain events from REI and other’s from the flowershop. Which events can be carried on which channels is up to Tim.

- Respond to them independently. Tim might want to get notification events from the flowershop delivered to his phone today because it’s his wife’s birthday whereas normally merchant communications are sent to his mail box.

Tim is in charge of whether and how events are delivered. He manages the channel, delivery, and response while the publishers of these event choose the content.

This cannot be done within the bovine graces of any one company — not Apple, Facebook, Google or Microsoft — no matter how rich their services might be, and no matter how well they treat their users and customers. And not matter how much they might insist that they’re not really treating their users and customers as calves.

But they’re still playing the cow role, and we’re still stuck as calves. That’s why we keep looking for better cows.

For example take The Real Problem With Google’s New Privacy Policy, in Slate. The subtitle explains, “The tech giant owes users better tools to manage their information.” Well, that might be true. But we also need our own tools for managing relationships with Google — and every other site and service on the Web. And we need those tools to work the same way with every company, rather than different ways with every company.

(We have this, for example, with email, thanks to open, standard and widely deployed protocols. Email is fully human, even if we submit to playing the half-calf role inside, say, Gmail. We can still take our whole email pile outside of Gmail and put it on any other server, or host it ourselves. Email’s protocols and standards support that degree of independence, and therefore of humanity as well.)

Another example is The Ecommerce Revolution is All About You, in TechCrunch. Here’s the closing paragraph:

So shoppers, be prepared to give up your data. In the coming year, we’re going to see many more retail sites ramping up data-driven discovery. And e-commerce sites who aren’t thinking about how to mine social and other forms of data are probably going to be left in the dust by the Amazons and Netflix’s of the next wave of personalization.

Credit where due to Amazon and Netflix: their personalization is best-of-breed. Their breed just happens to be bovine.

As it did in 1995, Amazon today provides their own milk and cookies for their own calf-customers. As a loyal Amazon customer, I have no problem being its calf. But I can’t easily take my data (preferences, history, reviews etc.) from Amazon and use it myself, in my own ways, and for my own purposes. It’s their data, not mine.

The problem with this — for both Amazon and me — is that Amazon isn’t the whole World Live Web. I don’t shop only at Amazon, and I would like better ways of interacting with all sellers than any one seller alone can provide, even if they’re the world’s best online seller. (Which Amazon, arguably, is.)

So sure, the Ecommerce Revolution is “about us.” But if it’s our revolution, why aren’t we getting more of our own tools and weapons? Why should we keep depending on sellers’ personalization systems to do all the work of providing relevance for us as shoppers? Should we give up our data to those companies just so they can raise the click-through rates of their messages from one in less than a hundred to one in ninety-eight — especially when many of the misses will now be creepily “personalized” as well?

Shouldn’t we know more about what to do with our data than any seller can guess at? And if we don’t know yet, why not create companies that help us buy at least as well as other companies are help sellers sell?

Well, those kinds of companies are being created, and you’ll find a pile of them listed here, Kynetx among them.

VCs need to start looking seriously at development on the demand side. Kynetx is one among dozens of companies that are flying below the radar of too many VCs just looking at better cows, and better ways to sell — or worse, to “target,” “capture,” “acquire,” “lock in” and “manage” customers as if they were slaves or cattle.

The idea that free markets are your-choice-of-captor is a relic of a dying mass-market-driven mentality from the pre-Internet age. Free markets need free customers. And we’ll get them, because we’ll be them.

We — the customers — are where the money that matters most comes from. Driving that money into the marketplace are our own intentions as sovereign and independent human beings.

In the next few years we’ll build an Intention Economy, driven by customers equipped with their own tools, and their own ways of interacting with sellers, including their own terms of engagement. This was the promise of the Net and the Web in the first place, and we’ve awaited delivery for long enough.

Time’s up. The age of captivity is ending. Start placing your bets on the demand side.

Companies and customers need to be able to deal with each other in two ways: as individuals and as groups.

Companies and customers need to be able to deal with each other in two ways: as individuals and as groups.

The idea is to start getting real about what we’re all doing and not doing.

The idea is to start getting real about what we’re all doing and not doing.

For as long as we’ve had economies, demand and supply have been attracted to each other like a pair of magnets. Ideally, they should match up evenly and produce good outcomes. But sometimes one side comes to dominate the other, with bad effects along with good ones. Such has been the case on the Web ever since it went commercial with the invention of the cookie in 1995, resulting in a

For as long as we’ve had economies, demand and supply have been attracted to each other like a pair of magnets. Ideally, they should match up evenly and produce good outcomes. But sometimes one side comes to dominate the other, with bad effects along with good ones. Such has been the case on the Web ever since it went commercial with the invention of the cookie in 1995, resulting in a

The

The