My last post asked, How do you maximize the help that companies and customers give each other? My short answer is in the headline above. Let me explain.

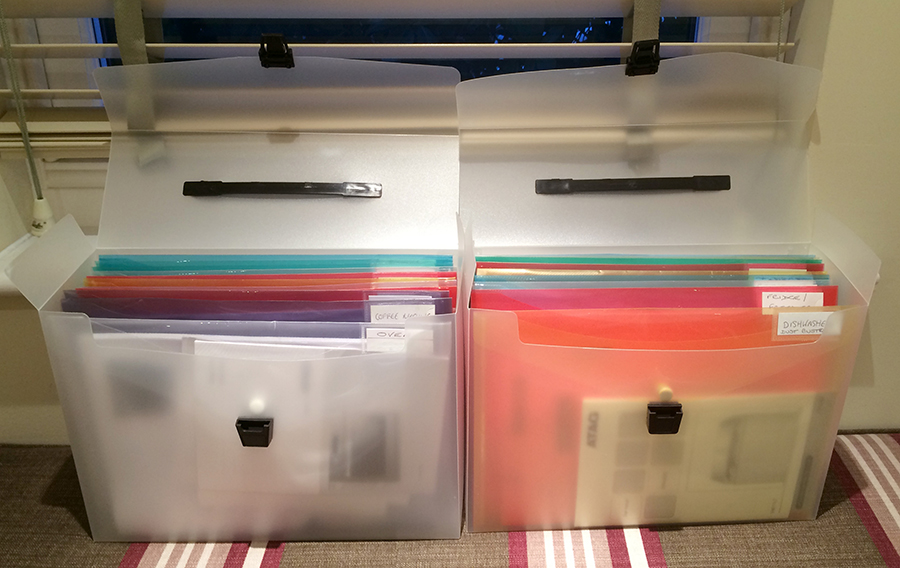

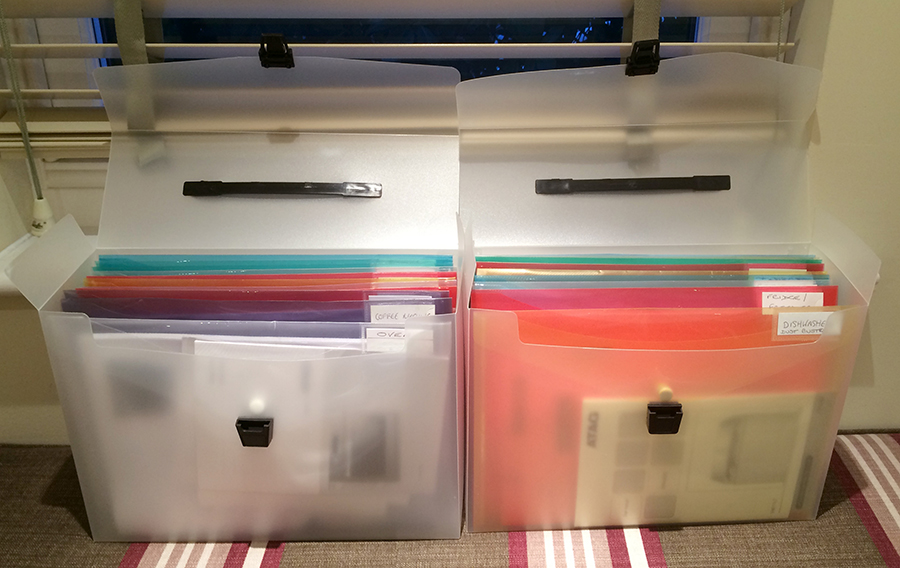

The house where I’m a guest in London has clouds for all its appliances. All the clouds are physical. Here they are:

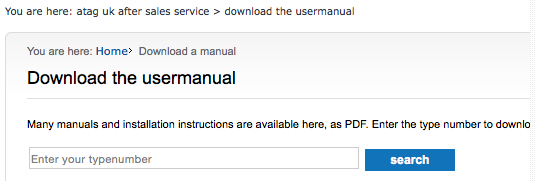

Here is a closer look at some of them:

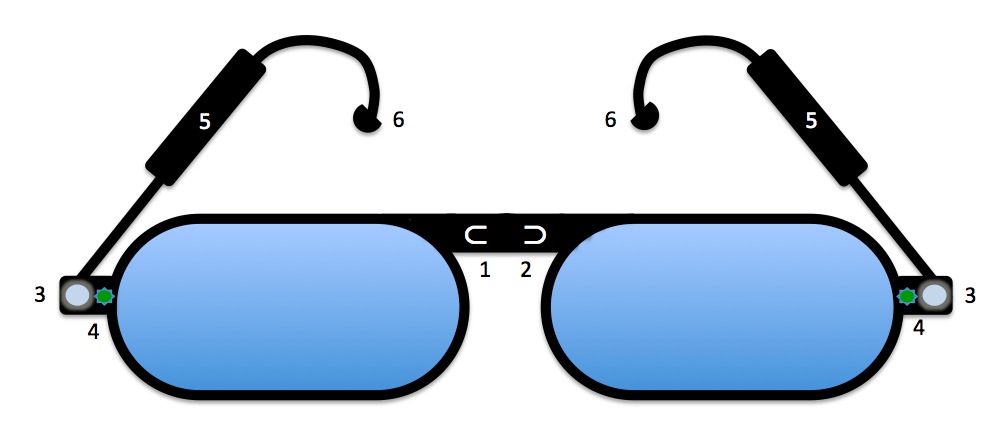

Each envelope contains installation and instruction manuals, warranty information and other useful stuff. For example, today I used an instruction manual to puzzle out what these symbols on the kitchen’s built-in microwave oven mean:

Now let’s say I didn’t have the directions handy. How would I find them? Obviously, on the Web, right? I mean, you’d think.

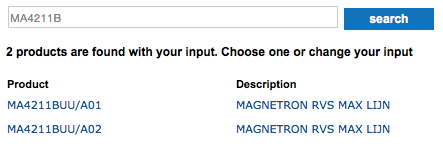

So I went to the site of Atag, the oven’s maker. From eyeballing the microwave, I gathered that the one in the kitchen is this one: the Combi-Microwave MA4211B. On the Atag website I found it buried in Kitchen Appliances —> Collection —> Microwaves, where it might also be the MA4211A or MA4211T. Hard to tell. Directions for its use appeared to be under Quality and Service —> Visit ATAG Service Support. There I found this:

When I clicked on “Download the User Manual,” I got this:

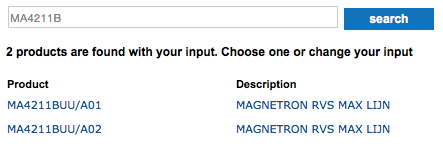

For “type number” I guessed MA4211B, entered it in the search field and got this:

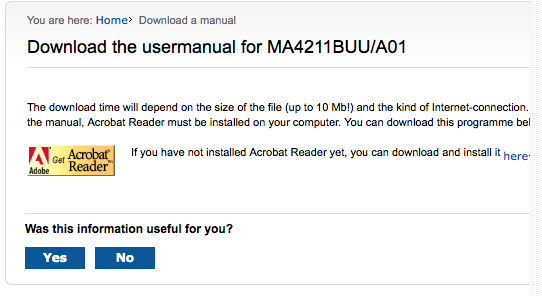

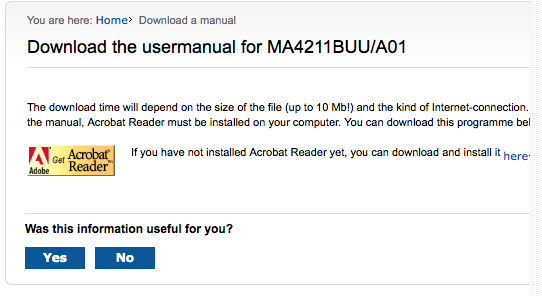

I got the same results clicking on both:

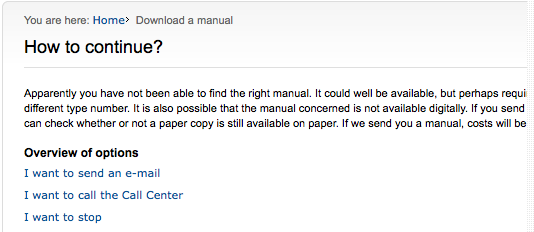

Nothing actually downloaded, and the Acrobat Reader information was useless to me. So I clicked on “No.” That got me this:

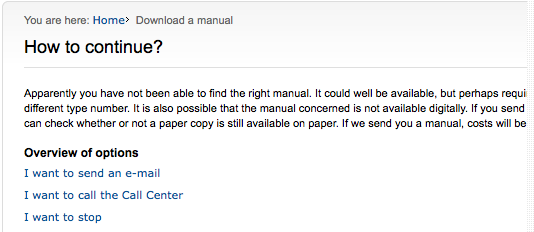

I then hit “I want to stop.” That looped me back to the search panel, three screenshots up from here.

In other words, a complete fail. Since the copyright notice is dated 2007 — eight years ago — I assume this fail is a fossil.

There are three reasons for this fail, and why its endemic to the entire service industry:

- The company bears the full burden of customer service.

- Every company serves customers differently.

- There is no single standard or normalized way for companies and customers to inform each other online.

What’s missing is a way to give customers scale — for the good of both themselves and the companies they deal with. Customers have scale with cash, credit cards, telephony, email and many other tools and systems. But not yet with a mechanism for connecting to any company and exchanging useful information in a standard way.

We’ve been moving in that direction in the VRM development community, by working on personal data services, stores, lockers, vaults and clouds. Those are all important and essential efforts, but they have not yet converged around common standards, protocols and customer experiences. Hence, scale awaits. What this house models, with its easily-accessed envelopes for every appliance, is a kind of scale: a simple and standardized way of dealing with many different suppliers — a way that is the customer’s own.

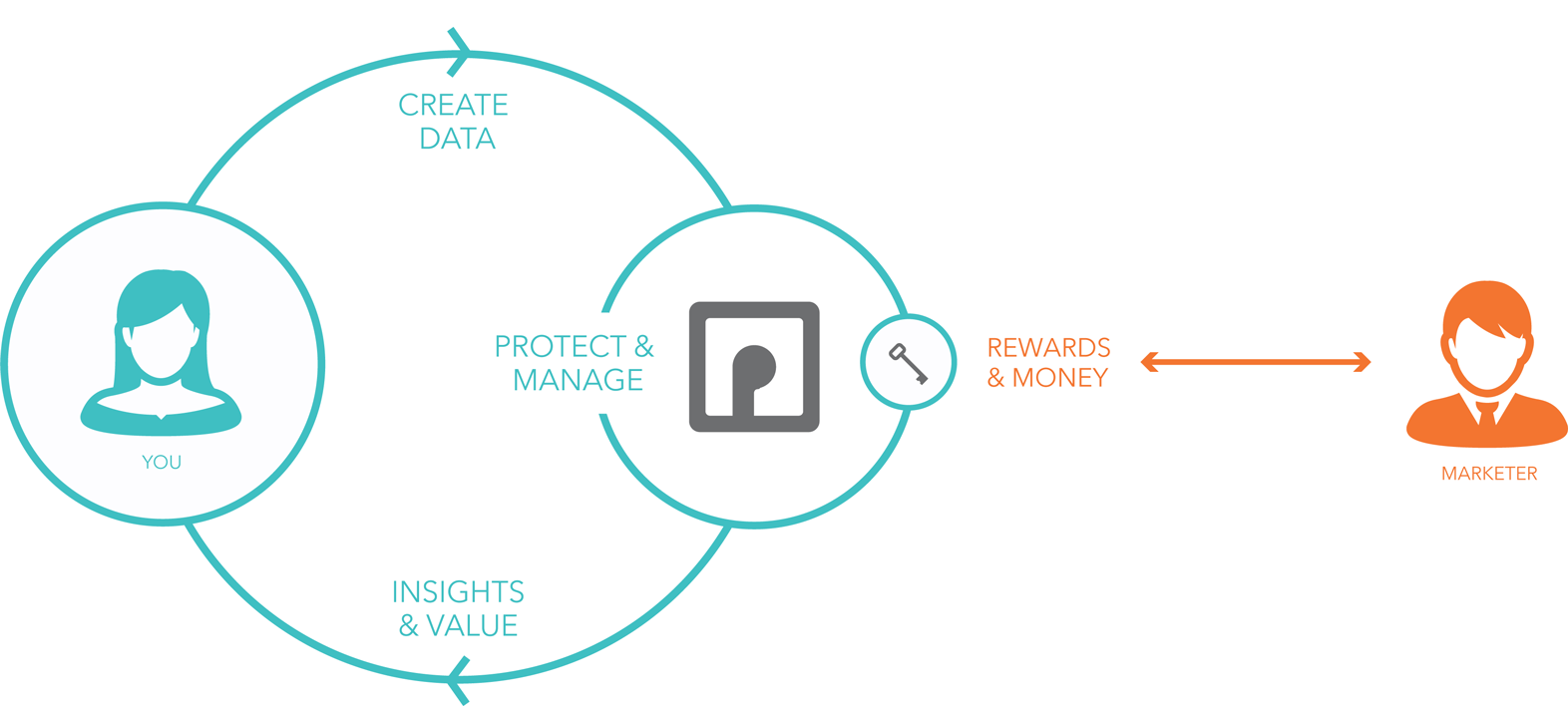

Now let’s imagine a simple digital container for each appliance’s information: its own cloud. In form and use, it would be as simple and standard as a file folder. It would arrive along with the product, belong to the customer*, and live in the customer’s own personal data service, store, locker, vault, cloud or old-fashioned hard drive. Or, customers could create them for themselves, just like the owner of the house created those file folders for every appliance. Put on the Net, each appliance would join the Internet of Things, without requiring any native intelligence on the things themselves.

There, on the Net, companies could send product updates and notifications directly into the clouds of each customer’s things. And customers could file suggestions for product improvements, along with occasional service requests.

This would make every product’s cloud a relationship platform: a conduit though which the long-held dreams of constant product improvement and maximized customer service can come true.

Neither of those dreams can come true as long as every product maker bears the full responsibility for intelligence gathering and customer support — and does those differently than every other company. The only way they can come true is if the customers and their things have one set of standard ways to stay in touch and help each other. That’s what clouds for things will do. I see no other way.

So let’s get down to it, starting with a meme/hashtag representing Clouds For Things : #CFT.

Next, #VRM developers old and new need to gather around standard code, practices and protocols that can make #CFT take off. Right now the big boys are sucking at that, building feudal fiefdoms that give us the AOL/Compuserve/Prodigy of things, rather than the Internet of Things. For the whole story on this mess, read Bruce Sterling‘s e-book/essay The Epic Struggle for the Internet of Things, or the chunks of it at BoingBoing and in this piece I wrote here for Linux Journal.

We have a perfect venue for doing the Good Work required for both IoT and CFT — with IIW, which is coming up early this spring: 7-9 April. It’s an inexpensive unconference in the heart of Silicon Valley, with no speakers or panels. It’s all breakouts, where participants choose the topics and work gets done. Register here.

We also have a lot of thinking and working already underway. The best documented work, I believe, is by Phil Windley (who calls CFTs picos, for persistent compute objects). His operating system for picos is CloudOS. His holdings-forth on personal clouds are here. It’s all a good basis, but it doesn’t need to be the only one.

What matters is that #CFT is a $trillion market opportunity. Let’s grab it.

* I just added this, because I can see from Johannes Ernst’s post here that I didn’t make it clear enough.

In

In  Meerkat

Meerkat Periscope

Periscope

In other words, the customer needs scale.

In other words, the customer needs scale.

is a piece by

is a piece by