We are now being farmed by business. The pretense of the “customer is king” is now more like “the customer is a vegetable” — Adrian Gropper

That’s a vivid way to put the problem.

There are many approaches to solutions as well. One is suggested today in the latest by @_KarenHao in MIT Technology Review, titled

An excerpt:

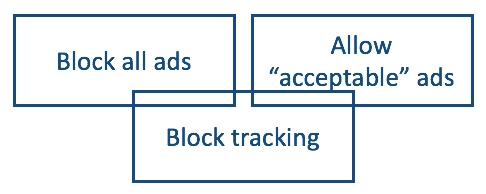

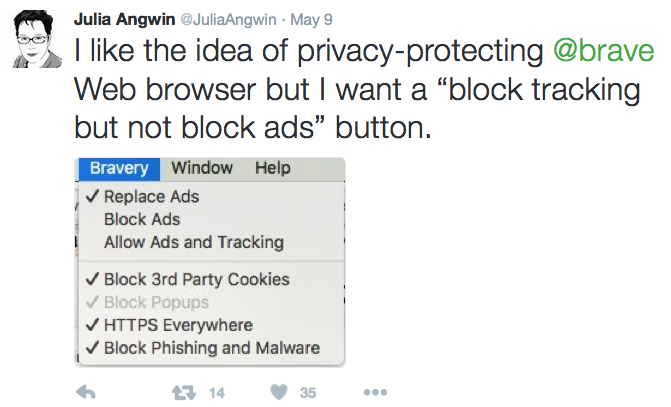

In a new paper being presented at the Association for Computing Machinery’s Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency conference next week, researchers including PhD students Nicholas Vincent and Hanlin Li propose three ways the public can exploit this to their advantage:• Data strikes, inspired by the idea of labor strikes, which involve withholding or deleting your data so a tech firm cannot use it—leaving a platform or installing privacy tools, for instance.• Data poisoning, which involves contributing meaningless or harmful data. AdNauseam, for example, is a browser extension that clicks on every single ad served to you, thus confusing Google’s ad-targeting algorithms.• Conscious data contribution, which involves giving meaningful data to the competitor of a platform you want to protest, such as by uploading your Facebook photos to Tumblr instead.People already use many of these tactics to protect their own privacy. If you’ve ever used an ad blocker or another browser extension that modifies your search results to exclude certain websites, you’ve engaged in data striking and reclaimed some agency over the use of your data. But as Hill found, sporadic individual actions like these don’t do much to get tech giants to change their behaviors.What if millions of people were to coordinate to poison a tech giant’s data well, though? That might just give them some leverage to assert their demands.

The sourced paper* is titled Data Leverage: A Framework for Empowering the Public in its Relationship with Technology Companies, and concludes,

In this paper, we presented a framework for using “data leverage” to give the public more influence over technology company behavior. Drawing on a variety of research areas, we described and assessed the “data levers” available to the public. We highlighted key areas where researchers and policymakers can amplify data leverage and work to ensure data leverage distributes power more broadly than is the case in the status quo.

I am all for screwing with overlords, and the authors suggest some fun approaches. Hell, we should all be doing whatever it takes, lawfully (and there is a lot of easement around that) to stop rampant violation of our privacy—and not just by technology companies. The customers of those companies, which include every website that puts up a cookie notice that nudges visitors into agreeing to be tracked all over the Web (in observance of the letter of the GDPR, while screwing its spirit), are also deserving of corrective measures. Same goes for governments who harvest private data themselves, or gather it from others without our knowledge or permission.

My problem with the framing of the paper and the story is that both start with the assumption that we are all so weak and disadvantaged that our only choices are: 1) to screw with the status quo to reduce its harms; and 2) to seek relief from policymakers. While those choices are good, they are hardly the only ones.

Some context: wanton privacy violations in our digital world has only been going on for a little more than a decade, and that world is itself barely more than a couple dozen years old (dating from the appearance of e-commerce in 1995). We will also remain digital as well as physical beings for the next few decades or centuries.

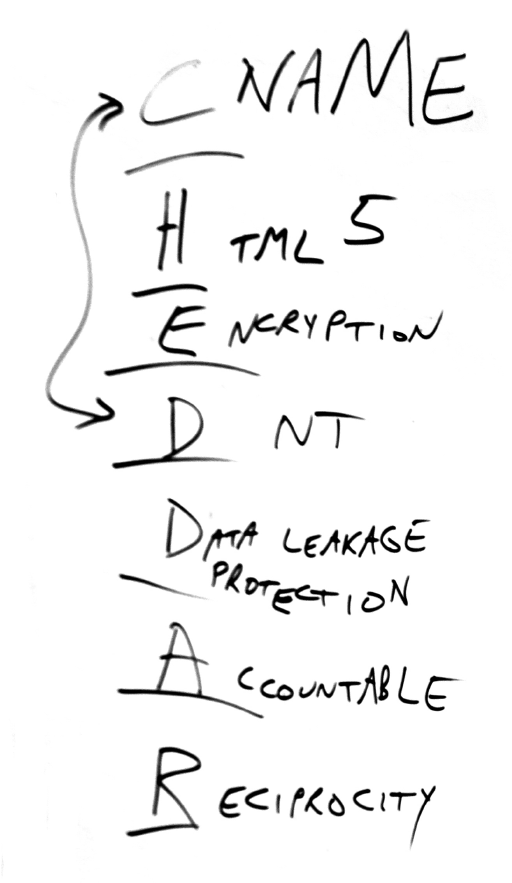

So we need more than these kinds of prescriptive solutions. For example, real privacy tech of our own, that starts with giving us the digital versions of the privacy protections we have enjoyed in the physical world for millennia: clothing, shelter, doors with locks, and windows with curtains or shutters.

We have been on that case with ProjectVRM since 2006, and there are many developments in progress. Some even comport with our Privacy Manifesto (a work in progress that welcomes improvement).

As we work on those, and think about throwing spanners into the works of overlords, it may also help to bear in mind one of Craig Burton‘s aphorisms: “Resistance creates existence.” What he means is that you can give strength to an opponent by fighting it directly. He applied that advice in the ’80s at Novell by embracing 3Com, Microsoft and other market opponents, inventing approaches that marginalized or obsolesced their businesses.

I doubt that will happen in this case. Resisting privacy violations has already had lots of positive results. But we do have a looong way to go.

Personally, I welcome throwing a Theia.

* The full list of authors is Nicholas Vincent, Hanlin Li (@hanlinliii), Nicole Tilly and Brent Hecht (@bhecht) of Northwestern University, and Stevie Chancellor (@snchencellor) of the University of Minnesota,

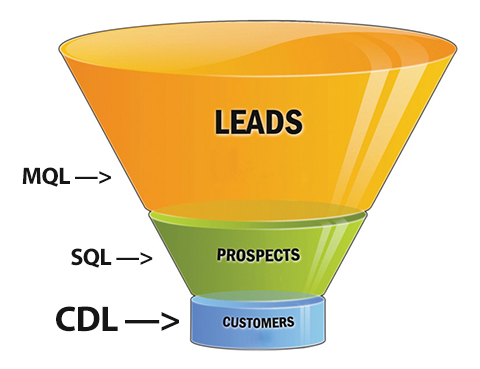

Imagine customers diving, on their own, straight down to the bottom of the sales funnel.

Imagine customers diving, on their own, straight down to the bottom of the sales funnel.

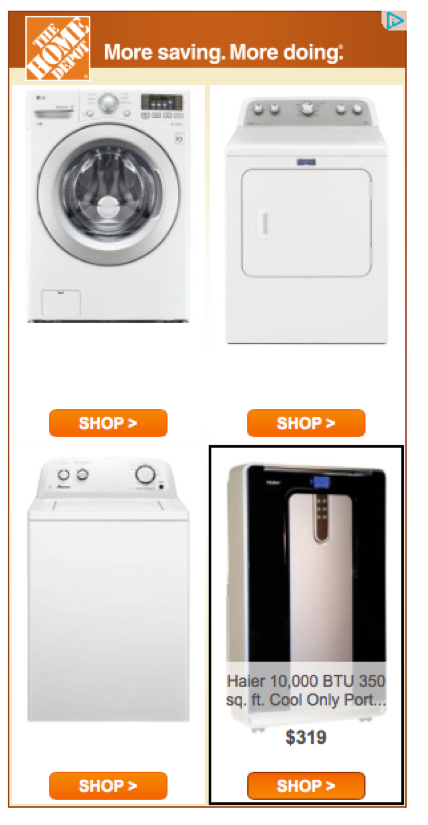

This is a shopping vs. advertising story that starts with the JBP Flip 2 portable speaker I bought last year, when Radio Shack was going bankrupt and unloading gear in “Everything Must Go!” sales. I got it half-off for $50, choosing it over competing units on the same half-bare shelves, mostly because of the JBL name, which I’ve respected for decades. Before that I’d never even listened to one.

This is a shopping vs. advertising story that starts with the JBP Flip 2 portable speaker I bought last year, when Radio Shack was going bankrupt and unloading gear in “Everything Must Go!” sales. I got it half-off for $50, choosing it over competing units on the same half-bare shelves, mostly because of the JBL name, which I’ve respected for decades. Before that I’d never even listened to one.

The program is called

The program is called

They also don’t want to be “

They also don’t want to be “