Lately a lot of thought, work and advocacy has been going into valuing personal data as a fungible commodity: one that can be made scarce, bought, sold, traded and so on. While there are good reasons to challenge whether or not data can be property (see Jefferson and Renieris), I want to focus on a different problem: the one best to solve first: the need for personal agency in the online world.

I see two reasons why personal agency matters more than personal data.

The first reason we have far too little agency in the networked world is that we settled, way back in 1995, on a model for websites called client-server, which should have been called calf-cow or slave-master, because we’re always the weaker party: dependent, subordinate, secondary. In defaulted regulatory terms, we clients are mere “data subjects,” and only server operators are privileged to be “data controllers,” “data processors,” or both.

Fortunately, the Net’s and the Web’s base protocols remain peer-to-peer, by design. We can still build on those. And it’s early.

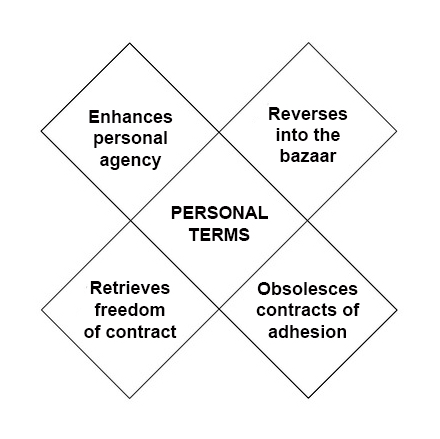

A critical start in that direction is making each of us the first party rather than the second when we deal with the sites, services, companies and apps of the world—and doing that at scale across all of them.

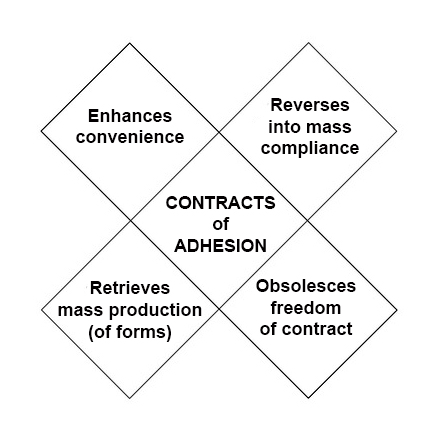

Think about how much more simple and sane it is for websites to accept our terms and our privacy policies, rather than to force each of us, all the time, to accept their terms, all expressed in their own different ways. (Because they are advised by different lawyers, equipped by different third parties, and generally confused anyway.)

Getting sites to agree to our own personal terms and policies is not a stretch, because that’s exactly what we have in the way we deal with each other in the physical world.

For example, the clothes that we wear are privacy technologies. We also have norms that discourage others from doing rude things, such as sticking their hands inside our clothes without permission.

We don’t yet have those norms online, because we have no clothing there. The browser should have been clothing, but instead it became an easy way for adtech and its dependents in digital publishing to plant tracking beacons on our naked digital selves, so they could track us like marked animals across the digital frontier. That this normative is no excuse. Tracking people without their conscious and explicit invitation—or a court order—is morally wrong, massively rude, and now (at least hopefully) illegal under the GDPR and other privacy laws.

We can easily create privacy tech, personal terms and personal privacy policies that are normative and scale for each of us across all the entities that deal with us. (This is what ProjectVRM’s nonprofit spin-off, Customer Commons, is about.)

It is the height of fatuity for websites and services to say their cookie notice settings are “your privacy choices” when you have no power to offer, or to make, your own privacy choices, with records of those choices that you keep.

The simple fact of the matter is that businesses can’t give us privacy if we’re always the second parties clicking “agree.” It doesn’t matter how well-meaning and GDPR-compliant those businesses are. Making people second parties in all cases is a design flaw in every standing “agreement” we “accept.” And we need to correct that.

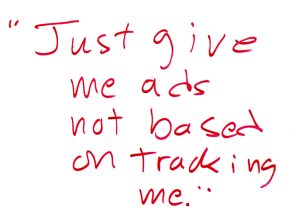

The second reason agency matters more than data is that nearly the entire market for personal data today is adtech, and adtech is too dysfunctional, too corrupt, too drunk on the data it already has, and absolutely awful at doing what they’ve harvested that data for, which is so machines can guess at what we might want before they shoot “relevant” and “interest-based” ads at our tracked eyeballs.

Not only do tracking-based ads fail to convince us to do a damn thing 99.xx+% of the time, but we’re also not buying something most of the time as well.

As incentive alignments go, adtech’s failure to serve the actual interests of its targets verges on absolute. (It’s no coincidence that more than a year ago, up to 1.7 billion people were already blocking ads online.)

And hell, what they do also isn’t really advertising, even though it’s called that. It’s direct marketing, which gives us junk mail and is the model for spam. (For more on this, see Separating Advertising’s Wheat and Chaff.)

Privacy is personal. That means privacy is an effect of personal agency, projected by personal tech and by personal expressions of intent that others can respect without working at it. We have that in the offline world. We can have it in the online world too.

Privacy is not something given to us by companies or governments, no matter how well they do Privacy by Design or craft their privacy policies. Top-down privacy simply can’t work.

In the physical world we got privacy tech and norms before we got privacy law. In the networked world we got the law first. That’s why the GDPR has caused so much confusion. Good and helpful though it may be, it is the regulatory cart in front of the technology horse. In the absence of privacy tech, we also failed to get the norms that would normally and naturally guide lawmaking.

So let’s get the tech horse back in front of the lawmaking cart. If we don’t do that first, adtech will stay in control. And we know how that movie goes, because it’s a horror show and we’re living in it now.

The

The difference between Phase One and Phase Two is

difference between Phase One and Phase Two is  Next steps in tracking protection and ad blocking. At the last VRM Day and IIW, we discussed

Next steps in tracking protection and ad blocking. At the last VRM Day and IIW, we discussed