(This post was updated and given a new headline on 20 April 2016.)

In The Compuserve of Things, Phil Windley issues this call to action:

On the Net today we face a choice between freedom and captivity, independence and dependence. How we build the Internet of Things has far-reaching consequences for the humans who will use—or be used by—it. Will we push forward, connecting things using forests of silos that are reminiscent the online services of the 1980’s, or will we learn the lessons of the Internet and build a true Internet of Things?

In other words, an Internet of Me (#IoM) and My Things. Meaning things we own that belong to us, under our control, and not puppeted by giant companies using them to snarf up data about our lives. Which is the #IoT status quo today.

A great place to work on that is IIW— the Internet Identity Workshop , which takes place next Tuesday-Thursday, April 26-28, at the Computer History Museum in Silicon Valley. Phil and I co-organize it with Kaliya Hamlin.

To be discussed, among other things, is personal privacy, secured in distributed and crypto-secured sovereign personal spaces on your personal devices. Possibly using blockchains, or approaches like it.

So here is a list of some topics, code bases and approaches I’d love to see pushed forward at IIW:

- OneName is “blockchain identity.”

- Blockstack is a “decentralized DNS for blockchain applications” that “gives you fast, secure, and easy-to-use DNS, PKI, and identity management on the blockchain.” More: “When you run a Blockstack node, you join this network, which is more secure by design than traditional DNS systems and identity systems. This is because the system’s registry and its records are secured by an underlying blockchain, which is extremely resilient against tampering and control. In the registry that makes up Blockstack, each of the names has an owner, represented by a cryptographic keypair, and is associated with instructions for how DNS resolvers and other software should resolve the name.” Here’s the academic paper explaining it.

- The Blockstack Community is “a group of blockchain companies and nonprofits coming together to define and develop a set of software protocols and tools to serve as a common backend for blockchain-powered decentralized applications.” Pull quote: “For example, a developer could use Blockstack to develop a new web architecture which uses Blockstack to host and name websites, decentralizing web publishing and circumventing the traditional DNS and web hosting systems. Similarly, an application could be developed which uses Blockstack to host media files and provide a way to tag them with attribution information so they’re easy to find and link together, creating a decentralized alternative to popular video streaming or image sharing websites. These examples help to demonstrate the powerful potential of Blockstack to fundamentally change the way modern applications are built by removing the need for a “trusted third party” to host applications, and by giving users more control.” More here.

- IPFS (short for InterPlanetary File System) is a “peer to peer hypermedia protocol” that “enables the creation of completely distributed applications.”

- OpenBazaar is “an open peer to peer marketplace.” How it works: “you download and install a program on your computer that directly connects you to other people looking to buy and sell goods and services with you.” More here and here.

- Mediachain, from Mine, has this goal: “to unbundle identity & distribution.” More here and here.

- telehash is “a lightweight interoperable protocol with strong encryption to enable mesh networking across multiple transports and platforms,” from @Jeremie Miller and other friends who gave us jabber/xmpp.

- Etherium is “a decentralized platform that runs smart contracts: applications that run exactly as programmed without any possibility of downtime, censorship, fraud or third party interference.”

- Keybase is a way to “get a public key, safely, starting just with someone’s social media username(s).”

- ____________ (your project here — tell me by mail or in the comments and I’ll add it)

In tweet-speak, that would be @BlockstackOrg, @IPFS, @OpenBazaar, @OneName, @Telehash, @Mine_Labs #Mediachain, and @IBMIVB #ADEPT

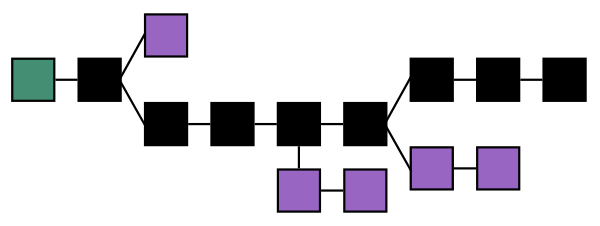

On the big company side, dig what IBM’s Institute for Business Value is doing with “empowering the edge.” While you’re there, download Empowering the edge: Practical insights on a decentralized Internet of Things. Also go to Device Democracy: Saving the Future of the Internet of Things — and then download the paper by the same name, which includes this graphic here:

Put personal autonomy in that top triangle and you’ll have a fine model for VRM development as well. (It’s also nice to see Why we need first person technologies on the Net , published here in 2014, sourced in that same paper.)

Ideally, we would have people from all the projects above at IIW. For those not already familiar with it, IIW is a three-day unconference, meaning it’s all breakouts, with topics chosen by participants, entirely for the purpose of getting like-minded do-ers together to move their work forward. IIW has been doing that for many causes and projects since the first one, in 2005.

Register for IIW here: https://iiw22.eventbrite.com/.

Also register, if you can, for VRM Day: https://vrmday2016a.eventbrite.com/. That’s when we prep for the next three days at IIW. The main focus for this VRM Day is here.

Bonus link: David Siegel‘s Decentralization.

Companies and customers need to be able to deal with each other in two ways: as individuals and as groups.

Companies and customers need to be able to deal with each other in two ways: as individuals and as groups.