We need a lexicon for the different ways buyers and sellers express their intentions to each other. Or, one might say, advertise.

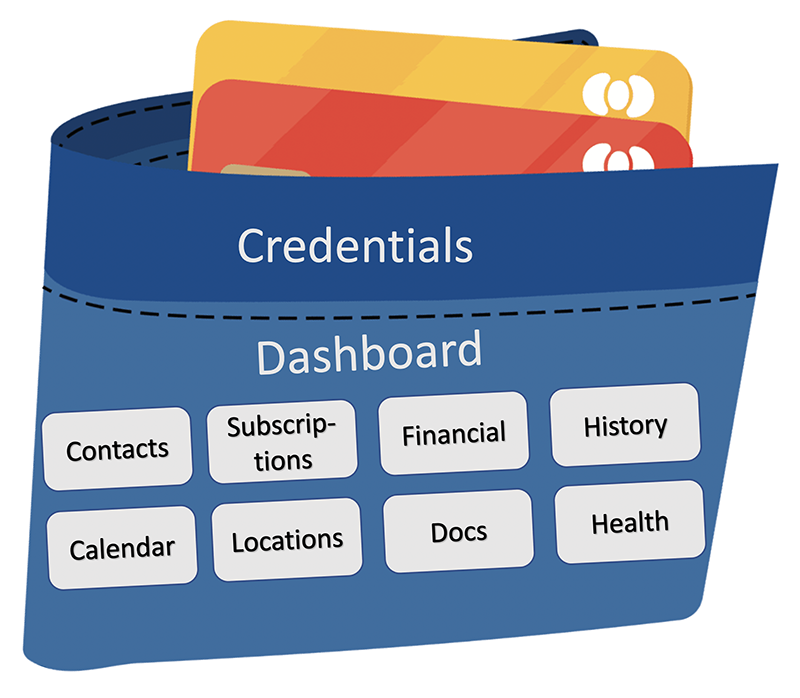

On the demand side (⊂) we have what in ProjectVRM we’ve called intentcasting and (earlier) personal RFP. Scott Adams calls it broadcast shopping and John Hagel and David Siegel both (in books by that title) call it pull.

On the sell side (⊃) I can list at least six kinds of advertising alone that desperately need distinctive labels. To pull them apart, these are:

- Brand advertising. This kind is aimed at populations. All of it is contextual, meaning placed in media, TV or radio programs, or publications, that appeal broadly or narrowly to a categorized audience. None of it is tracking-based, and none of it is personal. Little of it wants a direct response. It simply means to impress. This is also the form of advertising that burned every brand you can name into your brain. In fact the word brand itself was borrowed from the cattle industry by Procter & Gamble in the 1930s, when it also funded the golden age of radio. Today it is also what sponsors all of sports broadcasting and pays most sports stars their massive salaries.

- Search advertising. This is what shows up with search results. There are two very different kinds here:

- Context-based. Not based on tracking. This is what DuckDuckGo does.

- Context+tracking based. This is what Google and Bing do.

- Tracking-based advertising. I’ve called this adtech. Cory Doctorow calls it ad-tech. Others call it ad tech. Some euphemize it as behavioral, relevant, interest-based, or personalized. Shoshana Zuboff says all of them are based on surveillance, which they are. So many critics speak of it as surveillance-based advertising.

- Advertising that’s both contextual and personal—but only in the sense that a highly characterized individual falls within a group, or a collection of overlapping groups, chosen by the advertiser. These are Facebook’s Core, Custom and Look-Alike audiences. Talk to Facebook and they’ll tell you these ads are not meant to be personal, though you should not be surprised to see ads for shoes when you have made clear to Facebook’s trackers (on the site, the apps, and wherever the company’s tentacles reach) that you might be in the market for shoes. Still, since Facebook characterizes every face in its audience in almost countless ways, it’s easy to call this form of advertising tracking-based.

- Interactive advertising. Vaguely defined by Wikipedia here, and sometimes called conversational advertising, the purpose is to get an interactive response from people. The expression is not much used today, even though the Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB) is the leading trade association in the tracking-based advertising field and its primary proponent.

- Native advertising, also called sponsored content, is advertising made to look like ordinary editorial material.

The list is actually much longer. But the distinction that matters is between advertising that is tracking-based and the advertising that is not. As I put it in Brands need to fire adtech,

Let’s be clear about all the differences between adtech and real advertising. It’s adtech that spies on people and violates their privacy. It’s adtech that’s full of fraud and a vector for malware. It’s adtech that incentivizes publications to prioritize “content generation” over journalism. It’s adtech that gives fake news a business model, because fake news is easier to produce than the real kind, and adtech will pay anybody a bounty for hauling in eyeballs.

Real advertising doesn’t do any of those things, because it’s not personal. It is aimed at populations selected by the media they choose to watch, listen to or read. To reach those people with real ads, you buy space or time on those media. You sponsor those media because those media also have brand value.

With real advertising, you have brands supporting brands.

Brands can’t sponsor media through adtech because adtech isn’t built for that. On the contrary, adtech is built to undermine the brand value of all the media it uses, because it cares about eyeballs more than media.

Adtech is magic in this literal sense: it’s all about misdirection. You think you’re getting one thing while you’re really getting another. It’s why brands think they’re placing ads in media, while the systems they hire chase eyeballs. Since adtech systems are automated and biased toward finding the cheapest ways to hit sought-after eyeballs with ads, some ads show up on unsavory sites. And, let’s face it, even good eyeballs go to bad places.

This is why the media, the UK government, the brands, and even Google are all shocked. They all think adtech is advertising. Which makes sense: it looks like advertising and gets called advertising. But it is profoundly different in almost every other respect. I explain those differences in Separating Advertising’s Wheat and Chaff:

…advertising today is also digital. That fact makes advertising much more data-driven, tracking-based and personal. Nearly all the buzz and science in advertising today flies around the data-driven, tracking-based stuff generally called adtech. This form of digital advertising has turned into a massive industry, driven by an assumption that the best advertising is also the most targeted, the most real-time, the most data-driven, the most personal — and that old-fashioned brand advertising is hopelessly retro.

In terms of actual value to the marketplace, however, the old-fashioned stuff is wheat and the new-fashioned stuff is chaff. In fact, the chaff was only grafted on recently.

See, adtech did not spring from the loins of Madison Avenue. Instead its direct ancestor is what’s called direct response marketing. Before that, it was called direct mail, or junk mail. In metrics, methods and manners, it is little different from its closest relative, spam.

Direct response marketing has always wanted to get personal, has always been data-driven, has never attracted the creative talent for which Madison Avenue has been rightly famous. Look up best ads of all time and you’ll find nothing but wheat. No direct response or adtech postings, mailings or ad placements on phones or websites.

Yes, brand advertising has always been data-driven too, but the data that mattered was how many people were exposed to an ad, not how many clicked on one — or whether you, personally, did anything.

And yes, a lot of brand advertising is annoying. But at least we know it pays for the TV programs we watch and the publications we read. Wheat-producing advertisers are called “sponsors” for a reason.

So how did direct response marketing get to be called advertising ? By looking the same. Online it’s hard to tell the difference between a wheat ad and a chaff one.

Remember the movie “Invasion of the Body Snatchers?” (Or the remake by the same name?) Same thing here. Madison Avenue fell asleep, direct response marketing ate its brain, and it woke up as an alien replica of itself.

This whole problem wouldn’t exist if the alien replica wasn’t chasing spied-on eyeballs, and if advertisers still sponsored desirable media the old-fashioned way.

I wrote that in 2017. The GDPR became enforceable in 2018 and the CCPA in 2020. Today more laws and regulations are being instituted to fight tracking-based advertising, yet the whole advertising industry remains drunk on digital, deeply corrupt and delusional, and growing like a Stage IV cancer.

We live digital lives now, and most of the advertising we see and hear is on or through glowing digital rectangles. Most of those are personal as well. So, naturally, most advertising on those media is personal—or wishes it was. Regulations that require “consent” for the tracking that personalization requires do not make the practice less hostile to personal privacy. They just make the whole mess easier to rationalize.

So I’m trying to do two things here.

One is to make clearer the distinctions between real advertising and direct marketing.

The other is to suggest that better signaling from demand to supply, starting with intentcasting, may serve as chemo for the cancer that adtech has become. It will do that by simply making clear to sellers what buyers actually want and don’t want.

and original CEO of

and original CEO of