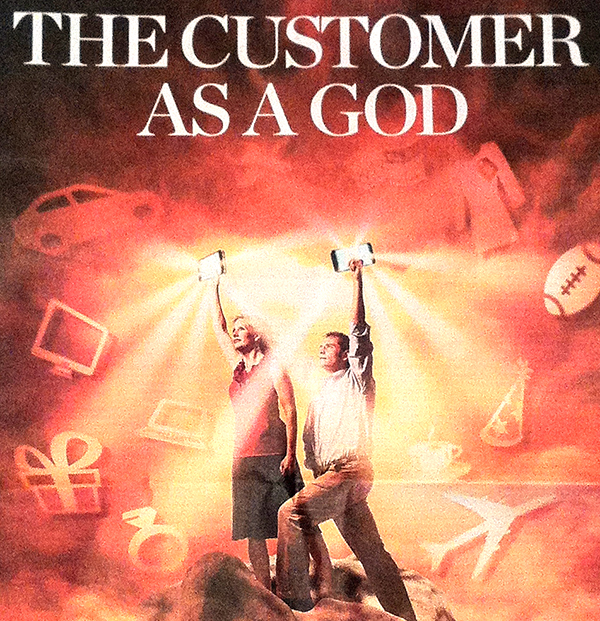

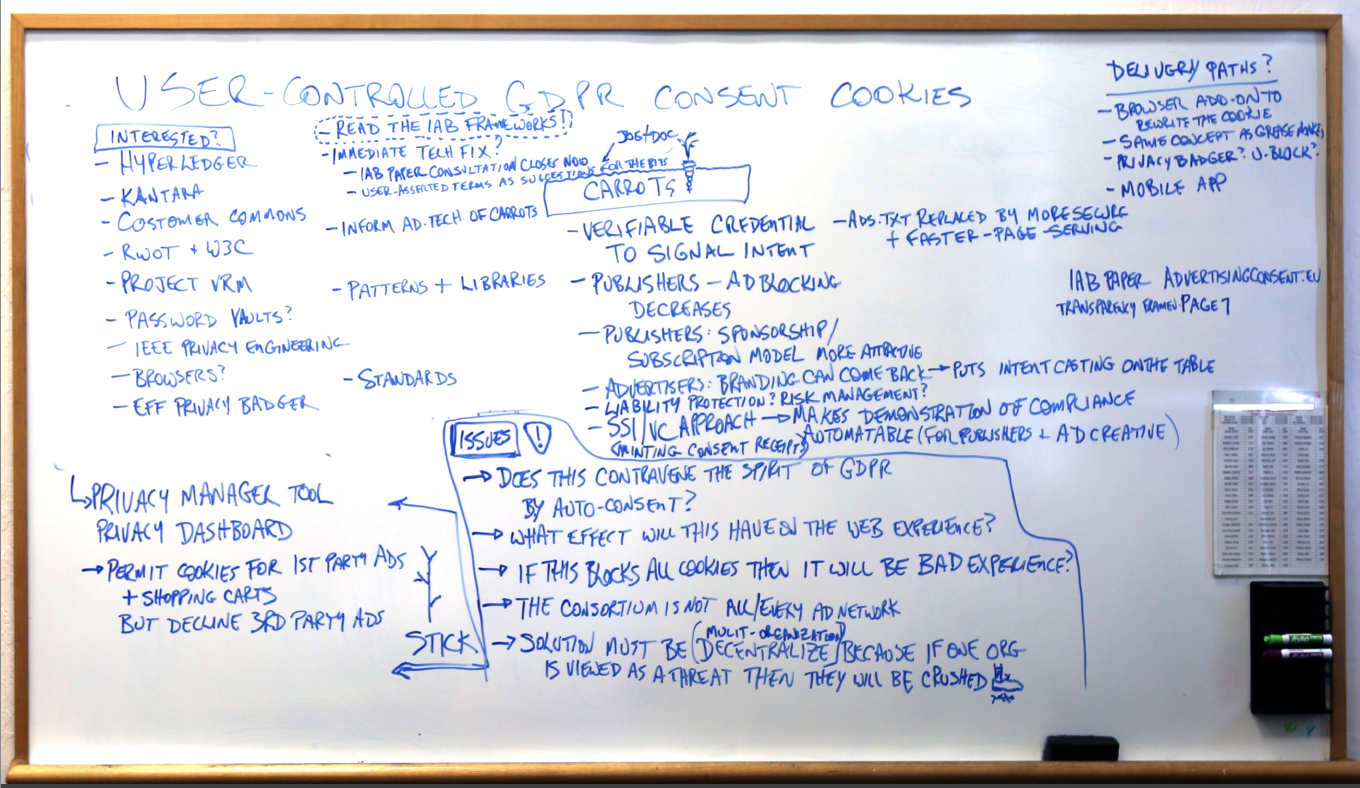

In Spring of 2012, Harvard Business Review Press published The Intention Economy: When Customers Take Charge. Not long after that, word came from The Wall Street Journal that Robert James Thomson, then Managing Editor of the paper, wanted to use the opening chapter of the book as a cover essay for the paper’s Review section. Amazon at the time was already giving that chapter away as a teaser for book sales, so I ended up compressing the whole book to a single 2000-word piece. Here’s how the cover looked:

I thought, “Holy shit, that looks like the cover of Dianetics or something.” Also, “I never would have used that headline.”

But that’s why they pay big bucks to headline writers. That one proved so terrific that I want to use it as the title of my next book, to follow up on The Intention Economy now that it’s finally about to happen.

The timing is right because tectonic shifts now shaking business were twelve years in the future when I started ProjectVRM (in Fall of 2006) and six years in the future when The Intention Economy came out.

Let’s frame those shifts with a pair of graphics from Larry Lessig‘s 1999 book Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace, and its successor in 2005, Code v2. The first is this dot, representing the individual:

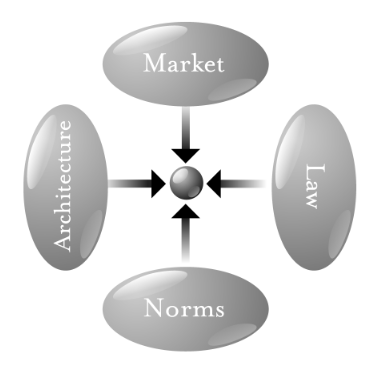

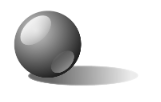

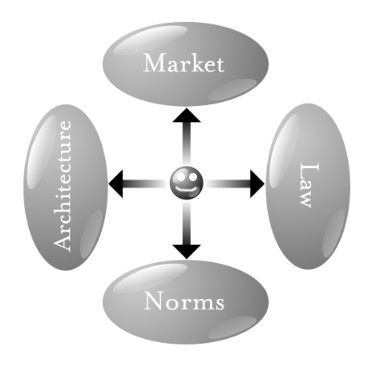

The second is this graphic, representing four constraints on the individual:

Each of those four ovals, Larry wrote, constrain or regulate what the individual can do in the networked world.

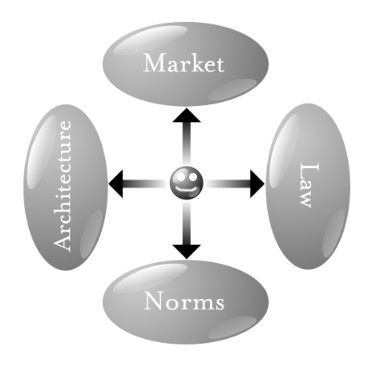

With ProjectVRM, our work is about turning around those arrows, empowering individuals to exert influence—or agency (the power to operate with full effect)—in all four directions:

In other words, to be a god.

In Code, Larry explains the four constraints with the example of smoking:

If you want to smoke, what constraints do you face? What factors regulate your decision to smoke or not?

One constraint is legal. In some places at least, laws regulate smoking—if you are under eighteen, the law says that cigarettes cannot be sold to you…

But laws are not the most significant constraints on smoking. Smokers in the United States certainly feel their freedom regulated… Norms say that one doesn’t light a cigarette in a private car without first asking permission of the other passengers…

The market is also a constraint. The price of cigarettes is a constraint on your ability to smoke —change the price, and you change this constraint…

Finally, there are the constraints created by the technology of cigarettes, or by the technologies affecting their supply… How the cigarette is, how it is designed, how it is built —in a word, its architecture—affects the constraints faced by a smoker.

Thus, four constraints regulate this pathetic dot—the law, social norms, the market, and architecture—and the “regulation” of this dot is the sum of these four constraints. Changes in any one will affect the regulation of the whole… A complete view, therefore, must consider these four modalities together.

But the Internet was not designed for pathetic dots. By specifying little more than how data is addressed and moved between any two points in the world, across any variety of networks, the Internet gave every conscious entity on that world a lever so huge Archimedes could only imagine it. I explain this in How tools for customers have more leverage than tools for business alone:

Archimedes said “Give me a place to stand and a lever long enough and I can move the world.”

Alas, Archimedes didn’t have that place. Now all of us do. It’s called the Internet.

Before the Internet, the best way to improve business was with better tools and services for businesses, or with new businesses to disrupt or compete with existing ones.

With the Internet, we can improve customers. In fact, that’s where we started when the Internet showed up in its current form, on 30 April 1995. (That’s when the Net could start supporting all forms of data traffic, including the commercial kind.) The three biggest tools giving customers leverage back then (and still today) were browsers, email and the ability to do anything any company could, starting with publishing.

But then we did what came most easily to business back in the Industrial Age: create new businesses and improve old ones. Nothing wrong with that, of course. Just something inadequate.

Worse, we created giant businesses that only gave customers leverage inside their walled gardens. By now we’ve lived so long inside Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon (called GAFA in Europe) that we can hardly think outside their boxes.

But if we do, we can see again what the promise of the Net was in the first place: Archimedes-grade power for everybody. And there are a lot more customers than companies in that population.

This is why a bunch of us have been working, through ProjectVRM, on tools that make customers both independent and better able to engage with business.

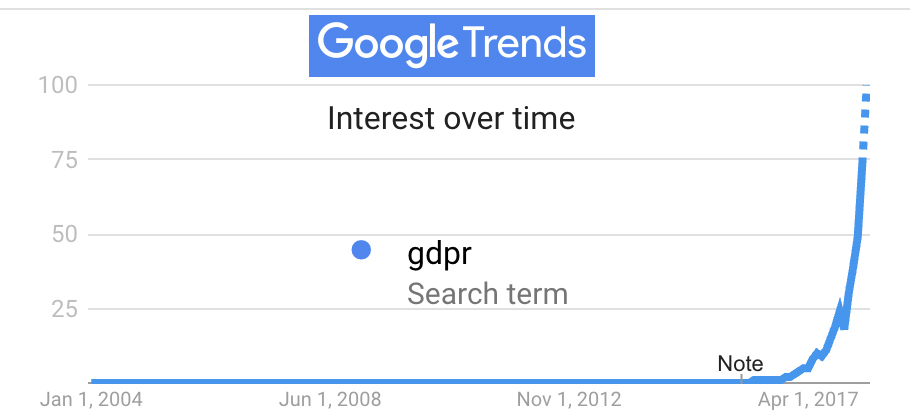

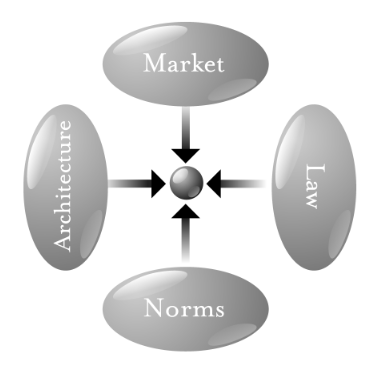

Now let’s look at one changed constraint: Law.

The tectonic shift happening there is the General Data Protection Regulation, or GDPR. It was created by the European Union to constrain what Shoshana Zuboff calls surveillance capitalism. Nearly all that surveillance is for the purpose of providing ways to aim ads at tracked eyeballs wherever they go. The GDPR forbids doing that, and imposes potentially massive fines for violations—up to 4% of global revenues over the prior year. I am sure Google, Facebook and lesser purveyors of advertising online will find less icky ways to stay in business; but it is becoming clear that next May 25, when the GDPR goes into full effect, will be an extinction-level event for tracking-based advertising (aka adtech) as a business model.

But there is a silver lining for advertising in the GDPR’s mushroom cloud, in the form of the oldest form of law in the world: contracts. These are agreements that any two parties can form with each other.

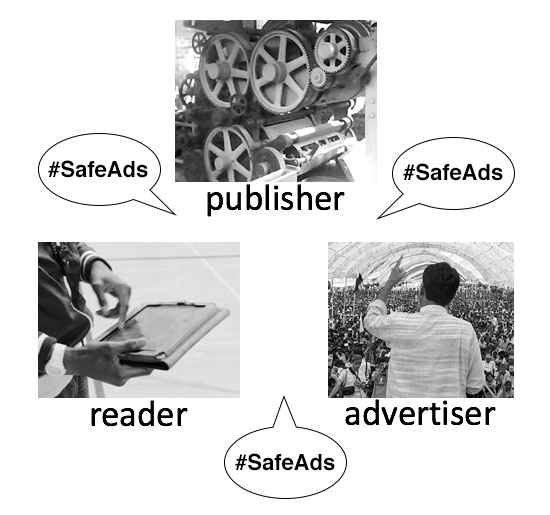

So, if an individual proffers a term to a publisher that says,

—and that publisher agrees to it, that publisher is compliant with the GDPR, plain and simple. (I unpack how this works in Good news for publishers and advertisers fearing the GDPR and in many other pieces in the People vs. Adtech series.)

—and that publisher agrees to it, that publisher is compliant with the GDPR, plain and simple. (I unpack how this works in Good news for publishers and advertisers fearing the GDPR and in many other pieces in the People vs. Adtech series.)

Those terms will live at Customer Commons, a non-profit spin-off of ProjectVRM. “CuCo” was created to do for personal terms what Creative Commons did, and still does, for personal copyright. (Creative Commons was a brainchild of Larry Lessig when he was a fellow at the Berkman Klein Center. We steal from the best.)

Our goal is to have our first agreement—the one two paragraphs up—working for both readers and publishers before the GDPR deadline in May. We have help toward that from the Cyberlaw Clinic at Harvard Law School and the Berkman Klein Center, from other friendly legal folk, and from equally friendly techies, such as those behind the JLINC protocol.

If publishers accept this olive branch from individuals (who are no longer mere “consumers” or “users”), it will demonstrate how existing law and a simple new architecture can alter both markets and norms in ways that make the world better for everybody.

In October 2016, I announced the end of ProjectVRM’s Phase One and the start of Phase Two.

Making VRM happen in 2018 will complete Phase Two. At the end of it our original thesis—that free customers are more valuable than captive ones—will either prove out or wait for other projects to do the job. Either way we’ll be done. All projects need an end, and this will be ours.

I believe free customers will prove more valuable than captive ones—to themselves, and to everyone else—for two reasons. One is that the Internet was designed to prove it in the first place (and no amount of screwage by governments or service providers can stuff that genie back in the bottle). The other is what I just tweeted here:

Services providing countless different ways for countless different businesses to provide good “customer experiences” () can’t answer the customer’s need for one way to deal with all of them. In fact, they only make things worse with every new login and “loyalty” program.

In other words, we need #customertech. Simple as that. That’s the lever that makes each of us an Archimedes. We’ll get it, from one or more of the projects and companies already on our developments list—and from others who will come along to answer a need that has been in the market since long before the Internet showed up.

So consider this is a recruitment post. We have a lot of work to do in a very short time.

ProjectVRM an award (there on the right) that was way ahead of its time.

ProjectVRM an award (there on the right) that was way ahead of its time.

—and that publisher agrees to it, that publisher is compliant with the GDPR, plain and simple. (I unpack how this works in

—and that publisher agrees to it, that publisher is compliant with the GDPR, plain and simple. (I unpack how this works in